Leadership•March 03, 2024

Skip to main content

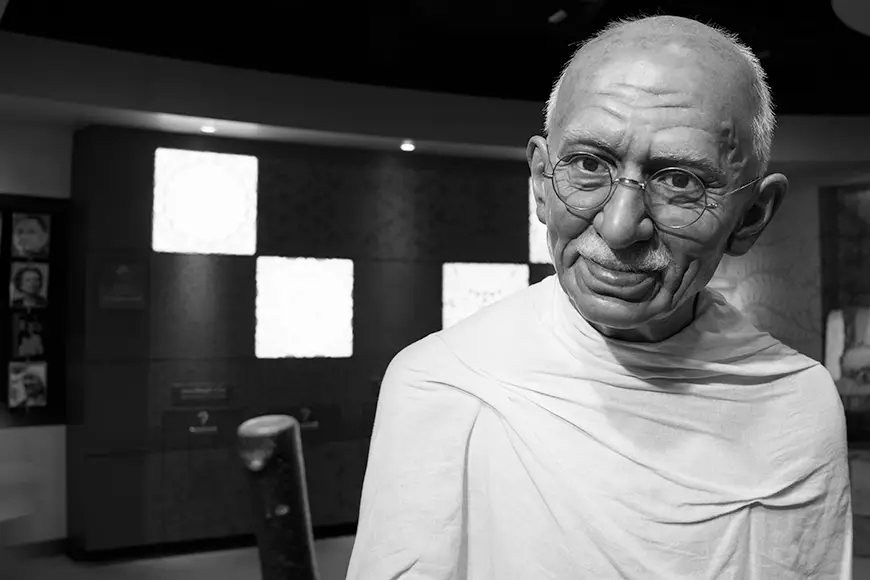

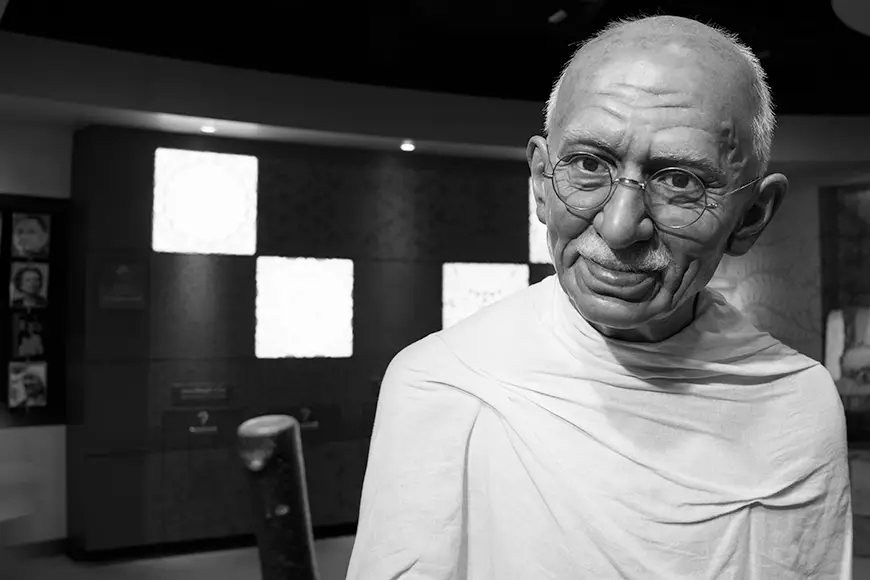

ON A BALMY MORNING IN THE SPRING OF 1930, Mohandas Gandhi set out to lead a procession of 78 people to march the 200 miles to India’s Western coast. As they walked, thousands joined the procession, where, on the eleventh anniversary of the 1919 Amritsar massacre, Gandhi led those gathered on the beach through the process of making their own salt.

This simple act profoundly and creatively challenged prevailing British law limiting the manufacture and sale of salt to only those whose businesses were licensed by British authorities.

This licensing regulation had enabled the British to tax even the poorest of the poor for the personal use of salt—a daily requirement for human functioning, especially in the heat of India. Gandhi’s leadership of the “Salt March” became a defining moment in the cultural transformation that was to culminate in India’s sovereignty.

The Spacious Center: Leadership and the Creative Transformation of Culture

Cultural leaders are able to transmute how they are personally affected by the culture into creative action that midwives the future.

Just four years after the Salt March, on another continent, Adolf Hitler was to orchestrate the massive spectacle of the Nuremberg Rallies in which 50,000 Nazi “labor servicemen” entranced thousands of German citizens.

The Nazis went to great effort to design elaborate speeches, banners, marching bands, and processions, staging these rallies against the backdrop of Nuremberg’s impressive architecture. The rallies were artfully filmed and broadcasted to further their intent as propaganda. The Nuremberg Rallies would find their place in history as a significant event in the coalescing of Nazi political and cultural domination.

Separated by only four years, Gandhi’s Salt March and Hitler’s Nuremberg Rallies were momentous historical events whose influence defined and determined the cultural changes that were to take place in subsequent years. In both cases, each leader envisioned major cultural transformation, and each chose to use large collective events as both a catalyst and an expression of his vision.

However, these two events were intrinsically different in their intentions and in their outcomes. The Salt March was an example of transgression structured as a creative ritual, while the Nuremberg Rallies were an example of repressive ritualism.

Through the Nuremberg Rallies, Hitler, a person who had once unsuccessfully sought admission into the most prominent school of art in Vienna, abused the transformative powers of art and ritual to intensify Germany’s cultural trance— a collective state of complacent passivity and loss of individuality. Conversely, Gandhi inspired an experience.

When the Center Falls Apart: Healing Modernity’s Cultural Trauma

The cultural center of the historical era that we refer to as “modernity” has collapsed. Its norms, values, and practices no longer have credibility and legitimacy. In the wake of this collapse, our planet’s ecological crisis calls for global cultural transformation.

The ways in which we consume and share our planet’s resources are ecologically unsustainable as well as painfully oppressive for millions of people. Extreme economic injustice and other oppressive conditions engender chronic conflict at a global level. Our contemporary challenge is to create a postmodern culture that once again has a center— a “spacious center” where the creative potentials of diversity, conflict, and chaos can be actualized.

After the traumatic cataclysms of the twentieth century, there is a great need for personal and social healing. As with personal healing, social healing requires us to awaken from the cultural trance that deadens us to what is possible.

Requiring from us the courage to turn toward our cultural trauma, creative cultural transformation can be an agonizing, dangerous, but also ecstatic ordeal that promises to restore what has been lost from that trauma.

Cultural Leadership: Choreographing the Dynamic Interaction Between Culture’s Center and Periphery

Our families, communities, organizations, and societies each have a distinct culture made up of a web of habits; this web can be imagined as having a center and a periphery. Viewed in this way, a family’s or organization’s culture is its habitat.

The center and periphery of a culture interact differently during steady-state periods and periods of change. During steady-state periods, the center of a culture is conventional—dense with rules, norms, taboos, and consensual notions of the “truth”—while the periphery is marginalized and remains disenfranchised, disempowered, and often scapegoated. In contrast, during periods of instability and conflict, the periphery is in dynamic interaction with a culture’s center.

During such times, the center is more responsive to the different and the unknown. By engaging and recognizing differences that were previously denied, suppressed, and trivialized, a culture’s web of habits transforms as it responds to the perspectives and practices found at the periphery.

The dynamic interaction between a culture’s center and its periphery keeps the culture vital and adaptive, providing cultural leaders with opportunities for creative cultural transformation. Cultural leaders choreograph this interaction in ways that are creative and transformative. In this way, cultural leadership is distinct from political and administrative leadership.

While political leaders primarily make rules and administrative leaders primarily enforce rules, cultural leaders like Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Mother Teresa find principled and imaginative ways to transgress those rules that inhibit the emergence of cultural sovereignty and creativity.

Their actions engender new and unexpected meanings. The recognition and creative transgression of rules and norms are at the heart of cultural leadership. Cultural leadership entails an ability to surrender through creative action to the necessities, meanings, and possibilities inherent in the present moment.

Cultural leaders are able to transmute how they are personally affected by the culture into creative action that midwives the future.

Engaging the Center: The Potency of Creative Transgression

Creative transgressions are a specific kind of creative action characterized by three distinct features. First, they involve principled actions. Second, they involve imaginative actions. Third, they entail conscious sacrifice.

A creative transgression is principled when it is aligned with the truth. It is this alignment that gives principled action its potency. Gandhi was able to transmute into creative action his painful awareness of Britain’s unjust, cruel, and exploitative taxation of the making and selling of salt.

Principled action necessitates that the transgressor has a passionate relationship with the truth. Although both Gandhi and Hitler used ritual as part of their strategy, Gandhi’s use of ritual was principled. A creative transgression is imaginative when it evokes a new and unexpected experience that requires others to reorient and make new meanings.

In addition to specific practical implications, the transgression has a symbolic impact. Because symbols are images that are condensed with meaning, new or revitalized symbols have the power to disrupt the prevailing cultural fundamentalism that exists at the conventional center of a culture. Gandhi focused on the salt laws, which symbolized British exploitation; his creative action of making salt symbolized cultural sovereignty.

A creative transgression typically entails the discipline of conscious sacrifice, requiring the willingness to experience difficulty, failure, and loss of privilege. Gandhi was an attorney, educated at the center of the British Empire. He went from being a conventional professional with a privileged life to a cultural leader clothed in simple white cotton, which he wove himself to protest the British control of textile production.

The Center Pushes Back: Meeting the Cultural Gatekeepers

As individuals and groups engage in cultural leadership, a culture’s center typically pushes back and resists the transformative potentials of the cultural leader’s creative action. At such times, cultural leaders are often discounted and scapegoated by the culture’s gatekeepers.

Cultural gatekeepers personify the restrictive and resisting forces within a culture that maintain the dominant ideology and ensure conformity with that culture’s rules, norms, values, and taboos. They personify a set of beliefs and practices that legitimize the status quo through the influence of political, economic, and media institutions.

As far back as we know, human communities have resorted to scapegoating as a way of exiling and marginalizing those who are different. Cultural leaders who challenge the center of a culture are likely to face such efforts at disempowerment and need to creatively respond in ways that continue building bridges between the center and its periphery.

Re-Creating the Center: The Cultural Leader as Creative Ritualizer

When the cultural center of a family, organization, or society fragments, there is a breakdown in the great transmission of human capacities—capacities such as compassion, courage, curiosity, and dignity—that is part of our evolutionary heritage.

Recreating a cultural center entails rekindling the sensitivities, interdependencies, reciprocities, and initiations that enable the generational continuity of these capacities. Fortunately, each time this great transmission fractures, the evolutionary gift of the human instinct to ritualize can serve to mend the broken connections. When we ritualize, we imaginatively deepen our participation in the necessities, meanings, and possibilities inherent in the present moment.

Creative ritual offers us an occasion to surrender to the guidance of spontaneously emerging images, enabling us to be carried by the river of imagination toward an unknown future. In this way, creative ritual engenders a context and container for principled and imaginative transgression so that the exiled, rejected, devalued, and difficult parts of our experience can express themselves in ways that have new meanings.

Through creative ritual, we are carried towards the future in spite of ourselves, even past our own resistance. Creative ritual is imagination in action, allowing us to tap into our indigenous knowing, thereby releasing the transformative potentials of our collective life.

In this way, the ritual evokes ecstatic and participatory consciousness. The transformation of culture and consciousness are inextricably intertwined. While cultural trauma entails a collective forgetting of difficult experiences, creative ritual supports us in facing the taboo aspects of those experiences, such as madness, grandiosity, greed, hate, cruelty, victimization, and failure. In part, cultural trauma is healed by ritualizing cultural shame about the defeats, failures, and losses of the past. In doing so, we come to realize the wisdom of failure.

Through ritualizing the difficult experiences of shame and failure, we activate our cultural memory, reversing the collective forgetting that cultural trauma induces. Gandhi strategically chose the anniversary of the Amritsar massacre as the day the procession arrived at the beach to make salt. Working with cultural trauma is a delicate and perilous process that requires a trustworthy context.

Creative rituals thus can evoke an experience of ritual trust, enabling profound collaboration among those participating. Ritual trust engenders a temporary suspending of fear, suspicion, indifference, conflict, and even hatred. The buoyancy of this liberating trust revitalizes connections among people, offering a touchstone to the potential of healing through friendship.

Such trust is susceptible to being eroded by the densities and resistances of the conventional center unless it is anchored within specific accountability processes and other cultural practices. As cultural trauma heals, prevailing ideologies dissolve. Creative ideas can then take hold within the space that begins to open at the center. In time, renewed cultural practices of accountability, forgiveness, reconciliation, and conviviality can emerge.

Imagination Triumphant: Sustaining a Spacious Center

Creative ritual, along with the ritual trust that it engenders, facilitates collaborative inquiry into our past, present, and future. The cultural leader then does not need to prescribe or predict the future, for it arises spontaneously—moment to moment with fresh immediacy and abundance. When our actions emerge from a spacious center, we begin to open to our collective destiny through creative engagement and collaborative surrender.

The spacious center is our gathering place where we sit face to face around the fiery and perilous gifts of the unknown, without the densities of certainty, trusting that the river of imagination will find and carry us.

About the author:

Aftab Omer, PhD, is the president of Meridian University. The University offers degree and professional programs globally, with an emphasis on the power of transformative learning. He is a sociologist, psychologist, developmentalist, and futurist. He spent his early life in Pakistan, India, Hawaii, and Turkey and received his education from M.I.T, Harvard and Brandeis universities. His publications have addressed a variety of topics, including transformative learning, dialogic capability, developmental power, cultural leadership, civil society, generative entrepreneurship, and the power of imagination. In his advising work, Omer focuses on team development and on leveraging the creative potentials of conflict, diversity, and complexity. He was the former president of the Council for Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies. He is a Fellow of the International Futures Forum and the World Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Learn More

Interested in learning more about the programs at Meridian?

Contact An Advisor »Attend an Info Session »

Submitting

Stay Inspired

Receive exclusive content on personal and professional transformation via email with expert insights in psychology, leadership, education, and more.

We don’t email frequently and you can always unsubscribe. By continuing, you are agreeing to Meridian’s Privacy Policy.